Cicada's Interface Architecture

Welcome to Cicada Note #1! Here I describe Cicada’s highest-level architecture.

If you haven’t yet read the brief introduction to Cicada you may want to do so here.

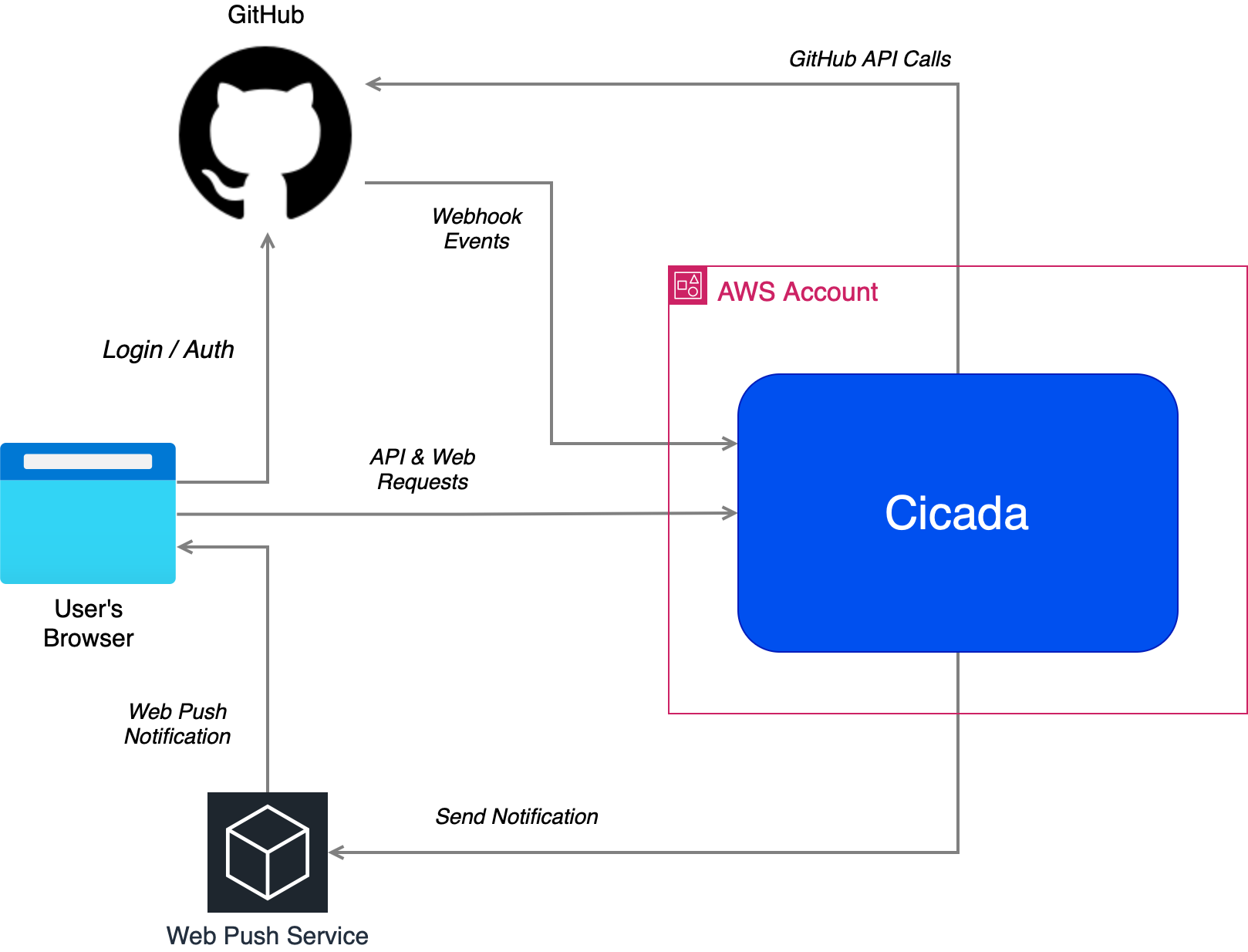

Cicada is an application that provides a user with real-time and historical data about their GitHub account, and also provides them with notifications about that account. The user interface to Cicada is a web application. The most simple architecture diagram for Cicada, showing the interfaces it has with the user’s browser and external services, looks like this:

Cicada's Interfaces

User’s Browser

First we have the user’s browser . As with all web applications Cicada’s user interface (UI) has to load various resources from a remote web server via HTTP web requests. And as is typical for many web applications Cicada’s UI also contains dynamic behavior that runs in the user’s browser to make HTTP API requests, and process the responses.

Much of the data that Cicada works with is proprietary - private data belonging to the user from their GitHub account. Therefore many of the requests that the user’s browser makes contain a token to prove the user’s identity. In order to obtain such a token the Cicada UI needs to perform an authentication process, which in Cicada’s case consists of Login and Authentication requests with both GitHub and Cicada itself.

The user’s browser can also receive web push notifications. Web push is a standard supported by all main browsers - both desktop and mobile based. Web push notifications alert the user that something has happened at a device level - i.e. whether or not they have the web application concerned open. I’ll describe more on why and how Cicada uses web push notifications in a future Cicada Note.

GitHub

Cicada provides information about a user’s GitHub Account. An account is either a personal account - where resources are owned by just one GitHub user, or it is an organization account, where resources are owned by a group of users. Cicada can work with both types of account.

In order to provide information about the user’s GitHub Account, Cicada needs to ingest data from GitHub - it does this both by pulling data from GitHub’s API, and by receiving data pushed by GitHub via Webhook events.

Finally, GitHub is a source of identity for login and authentication mechanisms - Cicada users “login with GitHub” in order to prove their identity for secure Cicada web and API requests.

Much of the work Cicada performs with GitHub uses its own GitHub App - a component within GitHub that configures permissions, webhook endpoints, and more.

Aside - Why not just a client application?

Cicada has a server-side component at all, rather than just being implemented as a client-side application, for two main reasons:

- GitHub doesn’t provide a way to subscribe comprehensively to real-time events without a server-side component. GitHub does include a feature for user notifications but this isn’t sufficient for Cicada’s behavior.

- Calls to GitHub’s API are rate-limited, and such rate-limiting is significant enough that polling the GitHub API for data from a user’s machine on a frequent enough basis to provide real(ish) time notifications will typically result in throttling for large organizations. Further, any cross-repository and/or historical behavior may also cause throttling.

Because of these reasons Cicada maintains a server-side real-time cache of GitHub data in a way that can be published to, and viewed by, many users.

Web Push Service

An intermediary web push service is used to send web push notifications to the user’s device. Cicada makes an API call to the web push service, and the service in turn sends the notification to the user. The specific web push service used for a notification will depend on data provided to Cicada when the user subscribes for notifications via an API request.

Cicada

For now whenever I just use the term “Cicada” in the context of a component in an architecture I’m usually going to be referring to the application deployed in Amazon Web Services. I could say “Cicada Service” or “Cicada Backend” but seeing as most of what Cicada does is in the cloud-deployed application (there’s not much browser-side code) it’s easier just to use “Cicada”.

Cicada processes the web and API requests from the user’s browser described earlier. It also processes webhook events from GitHub.

Cicada makes external calls to GitHub’s API - for user token validation and getting various data about accounts. It does so in the context of the permissions provided by the GitHub App described earlier.

Finally Cicada makes external calls to web push services, as described in the previous section.

Cicada could perform all of this work as one single application running in AWS EC2 or running on a virtual private server (VPS). And some people might even think that that’s the best way to implement it! But considering I’ve built Cicada to be an example of building serverless applications it’s actually implemented using a number of different services, which I’ll start describing in the next note - stay tuned!

Summing up

In this Cicada Note I described the highest level architecture of Cicada, showing the top-level components and the interfaces between them. The next Cicada Note drills into this architecture by one level to look at the primary AWS services used, and the interactions between them.

Feedback

I value hearing what people think about how I’ve built Cicada, and also my writing in Cicada Notes. If there ends up being enough interest I’ll start some kind of discussion forum, but for now please either email me at mike@symphonia.io, or if you’re on Mastodon then please kick off a discussion there - my user is @mikebroberts@hachyderm.io .