AWS beyond the sandbox - moving to a multi-Account Organization

One of the great things about Amazon Web Services is that anyone with a bank card can create an Account. This is how a lot of companies start their AWS journey - someone signs up using a corporate credit card, and then starts building.

This works fine for the first 2 or 3 developers in a company experimenting together. Eventually though someone will want to deploy a production application, or give access to a few more people, or need to create a VPC so that they can use a database, or “start thinking about security”. Any of these things need some careful thought, and this is the time that companies start to think about organization operations, whether they realize it or not.

I use the term Organization operations (or Org Ops) to refer to all the “infrastructure” work that people do that impacts or touches multiple deployment environments, applications, or teams. Why do I call it organization operations? Because activities that come under this banner are often bounded by the biggest context that AWS has which is (drum roll…) an Organization. “But wait” you might say “when I signed up to AWS with that credit card did I create an Account or an Organization?”, the answer to which, of course, is “yes”.

If this answer confuses you, or you care about any of the needs I mentioned above, or if you’ve inherited an almighty mess of a Clickops AWS nightmare that Cthulhu would be proud of and you need to start bringing some sanity to the chaos, then I believe I can help you!

Welcome to my AWS Org Ops series

This is the first of several articles focused on how I manage AWS operations at small-medium company scale. Since AWS Accounts and Organizations are the most fundamental aspects of this work I’m starting with them. For the remainder of this article I explain the following:

- What, precisely, are AWS Accounts and Organizations?

- Why should you use a multi-Account AWS Organization?

- How should you plan your Organization?

What are Organizations and Accounts?

First of all I need to clear up that question about what it is you create when you first sign up for AWS. But to do that I need to tell a story. Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin…

Singleton AWS Accounts

When you sign up in AWS what you get as a reward for handing over your credit card details is an Account, and a root user - an email address and password that gives you full access to the Account.

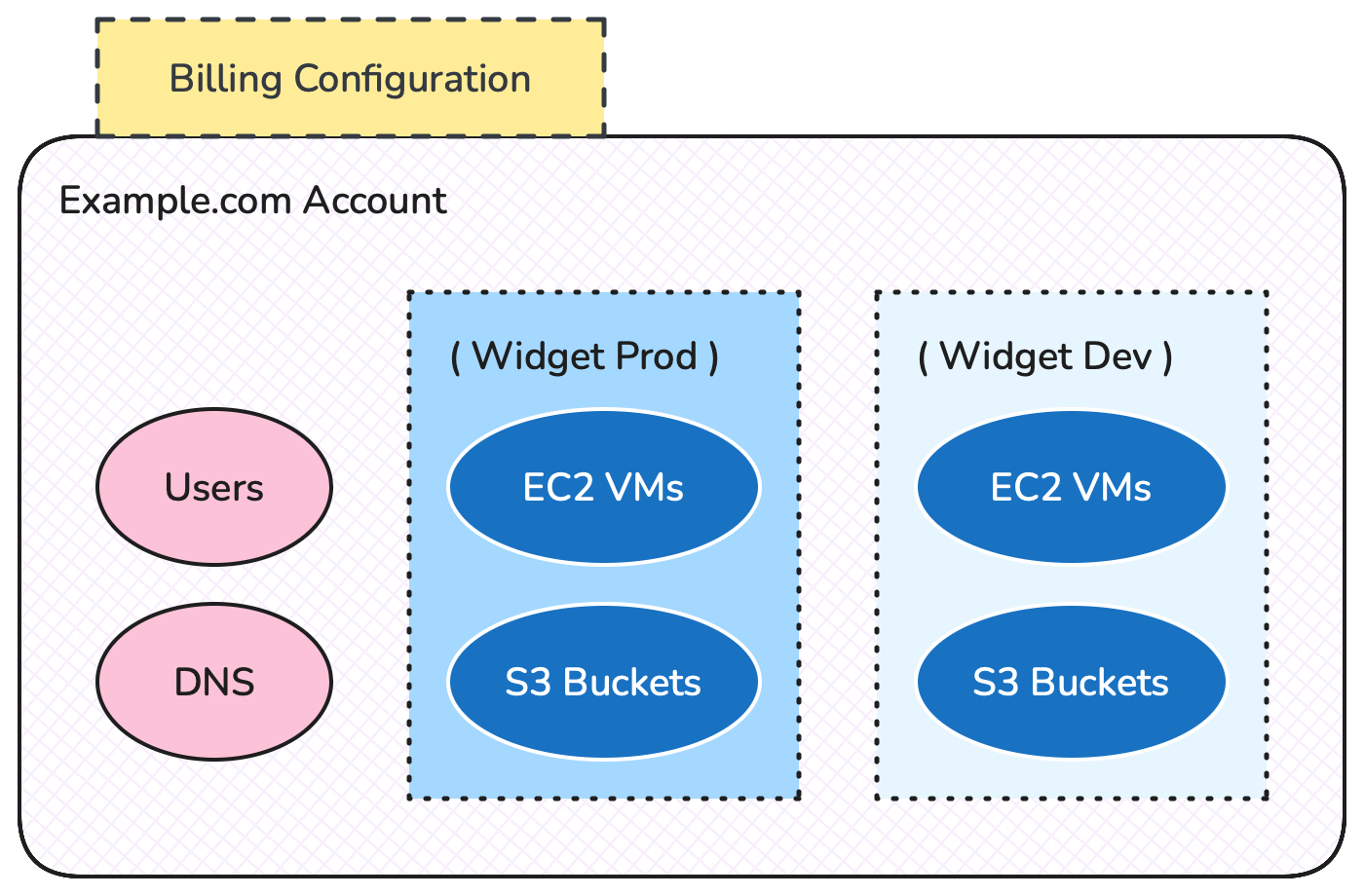

This Account performs several duties, two of which are:

- It’s the parent container of every resource you create - users, EC2 machines, security policies, etc.

- It defines how you pay AWS, via billing configuration

Single AWS Account with all resources

Back in the dim and distant past of the late 2000s this was basically the entire story regarding AWS Accounts - every Account was isolated, every Account had its own billing, and every company had one Account. But there are sharks lurking beneath this seemingly gentle sea.

The problems of using a single AWS Account

First, say you want developers to have full access to creating, modifying, and deleting S3 buckets for their development workloads - that’s fine, you can just give their users admin access to all the S3 buckets in the Account. But what about production buckets, those need to be secured so that developers can’t delete the contents, and depending on what the buckets store some developers might not even be given read access.

If the production buckets are in the same Account as the development buckets then you have to grant read-only permissions (or no permissions at all) on a bucket-by-bucket basis to the production buckets. But what happens if you have 100s or 1000s of buckets? Per-bucket permissions quickly become a horrible time-suck. You can set permissions based on name prefixes, but this is brittle and highly likely to have problems.

Further, the problems with using a single Account are not limited to security. Some services have Account-wide scope for technical limits or quotas. E.g. say you’re using AWS Lambda - Lambda has an Account-level limit for how many total Lambda function instances can be active in the Account at any one time - the concurrent executions limit. This starts out as 1000, which is sufficient for many cases. But say you’re performing a load test on your test environment, and are trying to simulate 10000 concurrent users - you might start to hit that Lambda limit, and when you do requests will fail. Which is fine for the load test, but what if your production environment is in the same AWS Account? It will also start to experience failures - all because of a test. Oops.

The Lambda concurrent executions limit can be increased on request, but keeping it small enough that it should satisfy any realistic production scenario can help you avoid burning a hole in your bank account should a mistake or security incident occur.

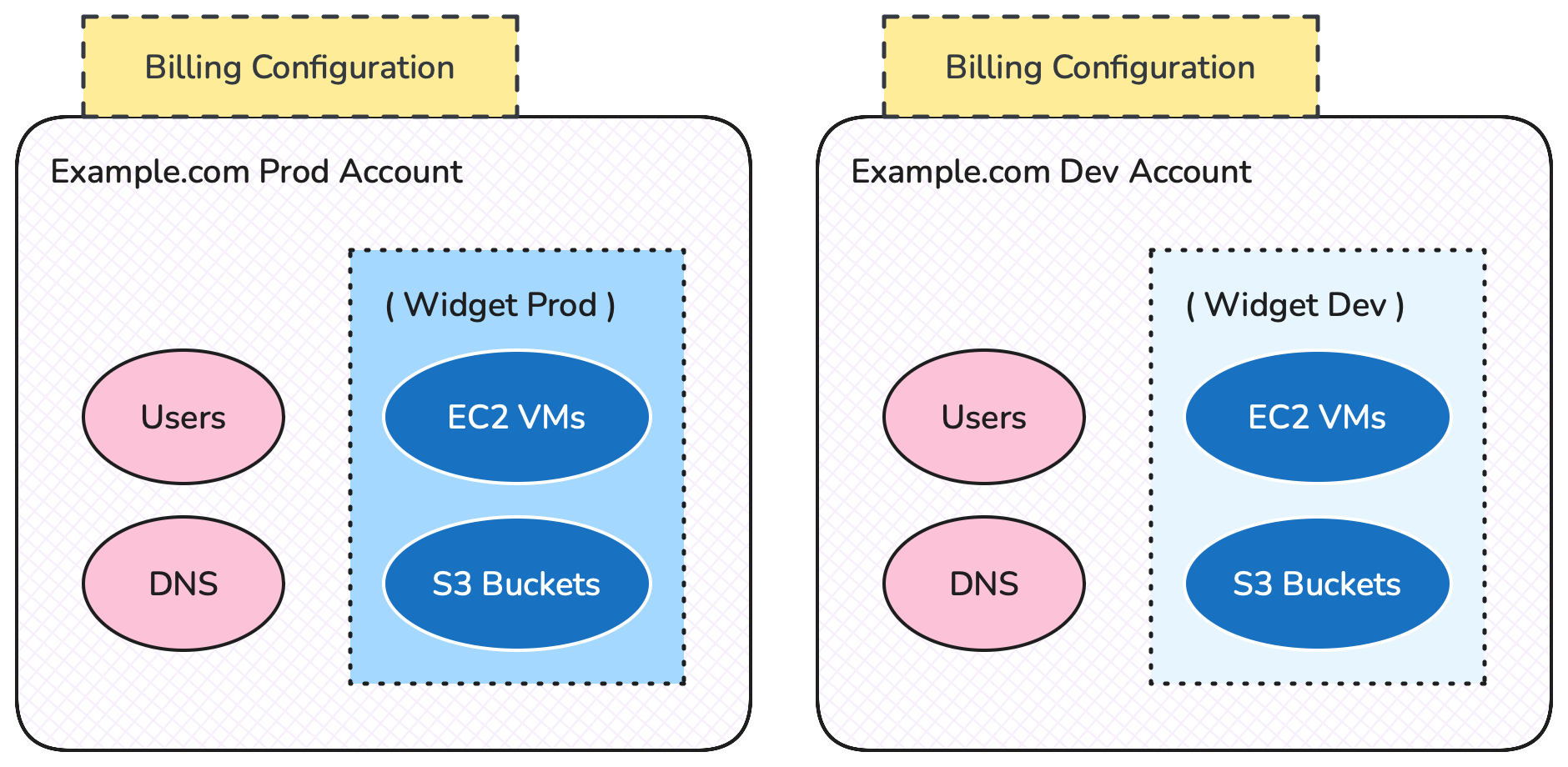

Not surprisingly companies started creating multiple AWS Accounts for different types of environment, or different workloads. But because every Account was an island (AKA a “singleton Account”) that meant setting up billing details - credit card numbers, billing contacts - for every Account. Finance departments hated this, and it also limited innovation by causing resistance to creating new Accounts for new applications.

Multiple isolated accounts

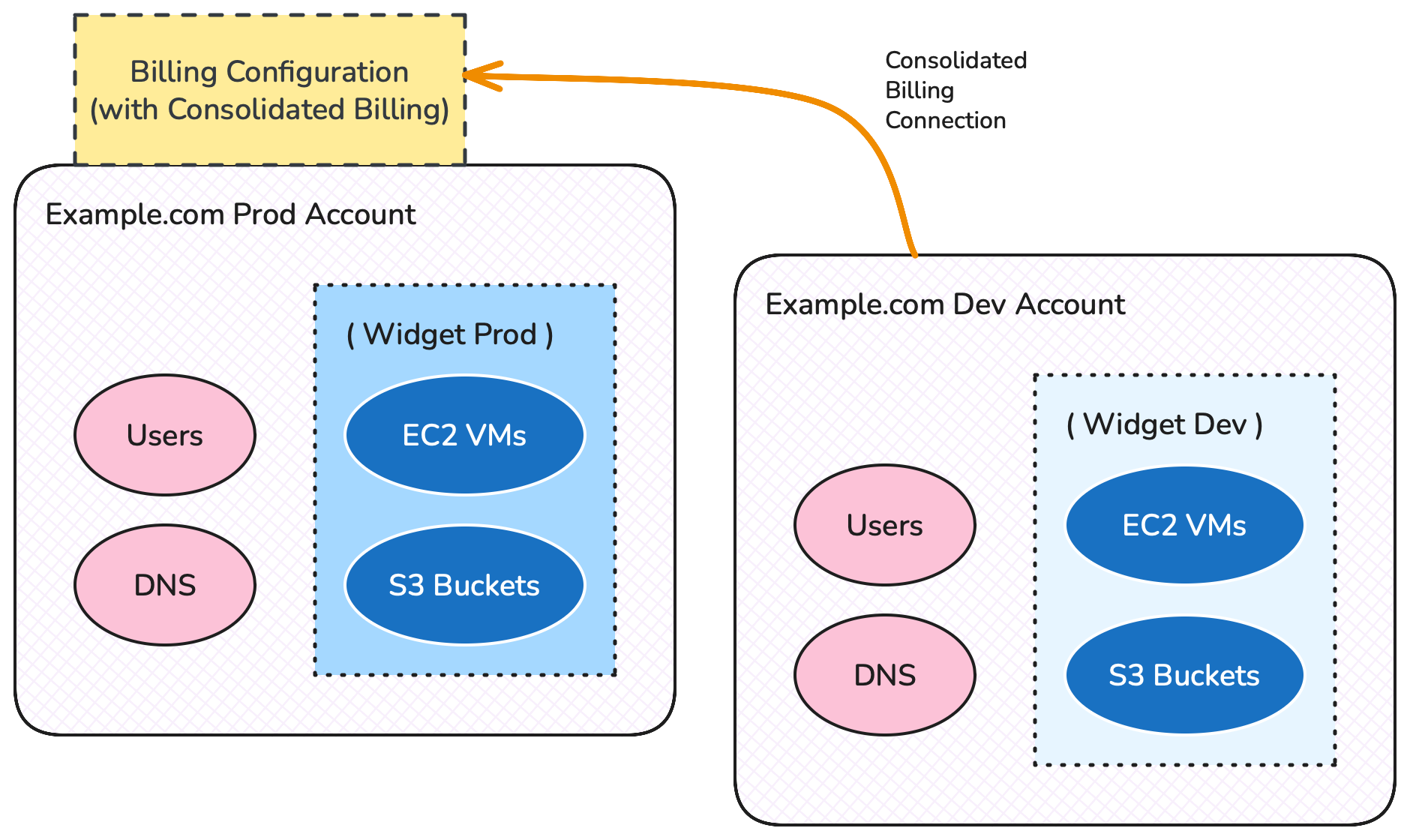

Amazon’s answer to this was Consolidated Billing.

Consolidated Billing

Yikes, this is dull for us software people. Was I an accountant in a past life?

To summarize the story so far - CTOs wanted multiple AWS Accounts because Accounts are a form of ring-fenced resource container, but CFOs didn’t want multiple AWS Accounts because it meant setting up billing contracts for each of them.

In 2010 AWS introduced the solution - Consolidated Billing. Simply put - one Account (the paying Account) had the billing configuration, and then the remainder of the Accounts were linked to the paying Account for the purpose of … well, paying. Now tech teams could create Accounts willy-nilly, and the finance team were happy because they didn’t need to setup a credit card every time.

Accounts with Consolidated Billing

Great! All problems solved! Accounts for everyone!

Well … kind of. The more people used multiple Accounts, the more certain operational activities started to get Very Annoying. Take user management for example (human users, not technical users provided for system-to-system integration). Back in the early 2010s typically you’d end up creating an AWS user per human per Account they needed access to. Alternatively you played some complicated, and never quite perfect, games with cross-Account permissions.

But now we have a new friction point to creating Accounts. If I’m a developer and I already have 3 different users for production, test, and development Accounts do I really want another set of 3 users for building a different application in a different set of Accounts?

A separate problem, which especially impacted larger companies, was when it came to setting default access to various AWS services in an Account (e.g. to stop people creating resources in far-away regions.) When you have 10s, 100s, or 1000s Accounts this becomes a lot of work, and keeping such defaults consistent was a huge headache.

So companies had all of these Accounts, which were totally independent (apart from billing, thanks 2010 AWS), but in “real life” they actually shared a lot of common behavior. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could model that behavior at an … organization scope?

AWS Organizations

When AWS created Consolidated Billing they effectively created the concept of an Account hierarchy. One Account was the parent Account which did the grown-up stuff of Dealing With Bills, and the child Accounts did … well, everything else.

Once you have a hierarchy though you can imagine doing other things, like:

- What if we allowed multiple levels of hierarchy? Then we could form an Account tree, and apply policies to different parts of the tree

- What if we allowed the parent Account to be responsible for other things that were cross-cutting through the company?

So in 2016 AWS introduced Organizations. Organizations, as a capability, is consolidated billing plus a whole lot more:

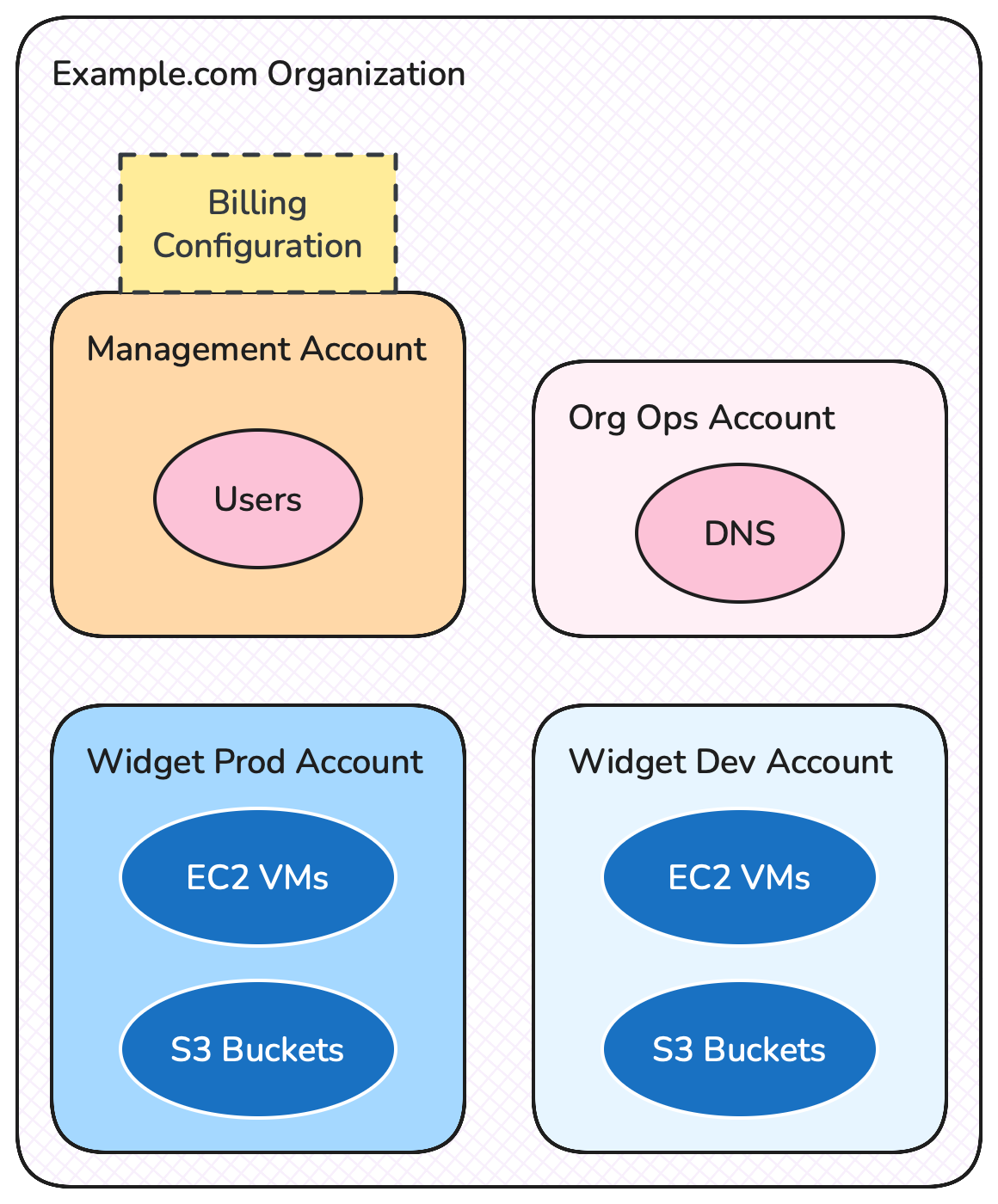

- The paying Account of consolidated billing became the Management Account of Organizations - in fact you’ll rarely see “consolidated billing” mentioned any more since it became just a part of AWS Organizations. The Management Account is the Account from which all other organizational things are managed (or delegated, which I’ll discuss in a future article). It is therefore a Very Important Account, and on the whole it’s usually best that you don’t do anything in it apart from Very Important Managementey Things.

- Organizations allows various services and capabilities to be configured in a cross-Account manner, scoped to the boundary of the Organization. Therefore things like human users, which in the real world are related to the entire company, can be configured once within the Organization and be used in all (allowed) Accounts in the Organization.

Accounts in an Organization

At first, in 2016, the only cross-Account capability beyond shared billing was being able to apply default service access via Service Control Policies on a hierarchical basis. For companies with large numbers of Accounts this was immediately a big benefit.

But why Organizations are so useful (for operations nerds like me) is that over time more and more capabilities have been added. If you look at this page you’ll see that dozens of different AWS services can be configured at an Organization-scope.

But what, specifically, is an AWS Organization?

AWS Organization concepts

Concretely, an AWS Organization consists of:

- One Management Account

- Zero or more Member Accounts

- Zero or more Organizational units (or OUs)

- Zero or more policies

Therefore the only thing an Organization must have is the Management Account. When you sign up for AWS and you get given the credentials for your first Account this is the Organization Management Account. And so finally I can explain my Very Funny (?) response from earlier - “yes”, you get both an Account and an Organization (consisting of just one Account) when you sign up to AWS.

Once you have a Management Account you can add Accounts to the Organization. These will usually be new Accounts that you’re creating in the context of the Organization, but can also be existing Accounts from outside of the Organization that you are moving into this Organization (every AWS Account is a member of one and only one Organization).

All of the member Accounts are structured in a hierarchy, organized by Organizational unit (OU). This hierarchy might be very simple - e.g. a flat structure with just the root OU - or can be an arbitrary tree.

Policies are various controls that are applied to the Organization - Service Control Policies being one example. When you’re getting started with Organizations you usually won’t need to worry too much about policies.

Finally one additional concept I want to mention - various Management Account activities can be delegated to specific member Accounts . Once you’ve started using this concept to its fullest you’ll often find you very rarely need to access the Management Account.

Strictly speaking you don’t actually have an Organization until you initialize it in the AWS Web Console, but that makes no difference from planning or billing points of view.

And that brings you pretty much up to date. Singleton Accounts, to Consolidated Billing, to a hierarchy of member Accounts in an Organization.

Why should you use a multi-Account Organization?

You should use multi-Account Organizations whenever you need to be concerned about the following:

- Different levels of security for different environment types or workloads

- Account-wide quotas, like the Lambda example I gave earlier

- Reducing risk of accidental change to production environments (because who among us hasn’t once deleted something they thought was a development resource, and it turned out they were wrong?)

In other words, you should use multi-Account Organizations pretty much as soon as you’re doing anything serious in AWS.

Some companies use different AWS Regions instead of different Accounts when splitting environments or workloads. I strongly recommend against this for various reasons. First - this only partially solves the problem areas, since some AWS services are global services which apply to all regions. IAM and Route53 (used for DNS) are two examples, and so your security issues don’t entirely go away when using multiple regions and one Account. Second - different regions will sometimes have different service capabilities (and always have different geo-related latency performance), and so if you’re (say) putting your production workloads in us-east-1 and test workloads in us-west-2 then this isn’t a true like-for-like comparison. And finally - it’s super easy to be in the wrong region in the AWS console and not realize, whereas with a different Account you explicitly have to go back to the Console Account picker, and click through to the new Account.

The one reason not to use multiple Accounts (or at least not too many of them)

There’s only one thing I don’t like about using multiple Accounts - AWS charges support per Account. So if you had one Account with business support that would cost $100 / month. But if you split that Account into five Accounts you now have to pay $500 / month.

Once you start spending enough with AWS this gets somewhat mitigated, but while you’re scaling up this is a frustrating counter-argument to AWS’ own recommended architectural practice.

My general suggestion is that it’s just something we have to suck up, but maybe don’t pick business support for all your Accounts - to get started basic support for developer Accounts might be sufficient.

How to plan your Organization

I’ve hopefully convinced you that you want to use multiple Accounts in your Organization, but how do you start? First, you need a plan.

AWS themselves describe the strategy and processes for managing an Organization as a Landing Zone. They even have a tool related to Landing Zones - Control Tower. I personally don’t use this term, or this tool, but it’s probably useful for you to know they exist.

What Accounts do you need?

Your first decisions are how many Accounts you need, and what should be in each of them. The answers depend a little on where you’re starting from, but my general recommendation for where you want to get to is as follows:

- Understand which Account is your Management Account, and expect to move as much as possible out of it. Usually a couple of things need to stay within the Management Account, for example human user management, if you’re using AWS Identity Centre.

- If this is going to be hard (e.g. because you already have production resources in the Account), consider creating a new AWS Management Account and Organization, and then move your existing Accounts under this new Organization. If you do this you may want to discuss with your AWS Account manager first so that they know what you’re doing, especially if you have any credits.

- Have an Account named

org-ops, and move as many of your cross-cutting resources here as you can. These are resource that aren’t specific to a product or service. Such resources typically include:- Root DNS (e.g. your top level DNS zones, like example.com)

- The company’s first, or “primary”, VPC - if you require VPC networking

- Audit logging (“CloudTrail”)

- Top-level users / roles for infrastructure automation (e.g. GitHub Actions OIDC)

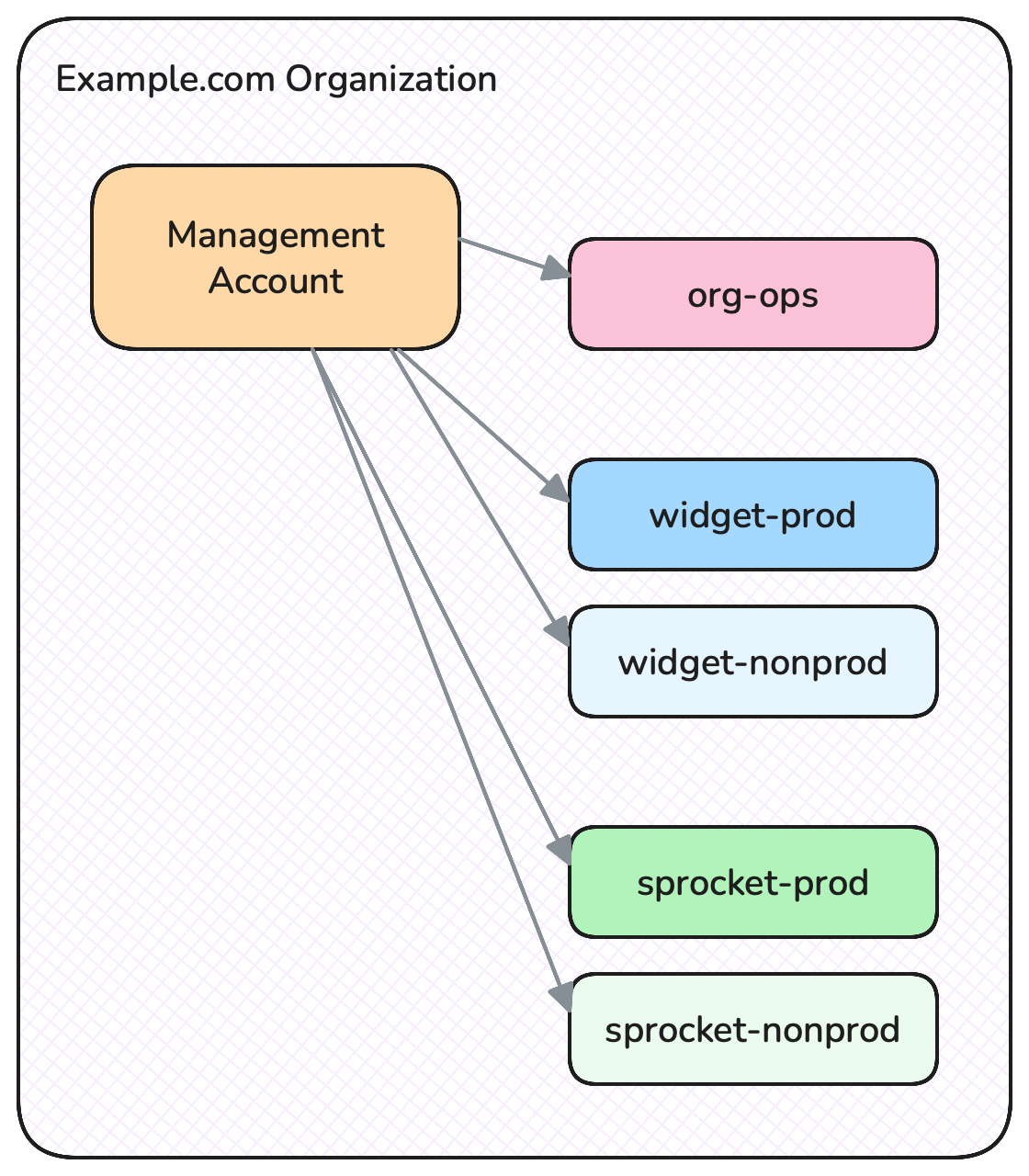

- Have separate Accounts per workload and per environment type. For example if you have a widget service and a sprocket service, I would create

widget-prod,widget-nonprod,sprocket-prod, andsprocket-nonprodAccounts.

Some notes on this:

- I’m going to explain the elements within the

org-opsAccount in later articles, but hopefully this should give you an idea what’s in theorg-opsAccount vs the workload Accounts - AWS’ recommended practice is to separate cross-organizational audit logging into a separate “audit” Account, and limit access. I think for small companies this is overkill, but you should likely discuss with whoever runs infosec in your company (if it isn’t you!)

- Many companies will split

nonprodAccounts intodevandtest, and I often do the same. In my examples above, instead of havingwidget-nonprodyou may instead havewidget-devandwidget-test. I recommend starting with two Accounts per workload, and grow to three if you need them, on a per-workload basis - you can always rename Accounts later. - Some companies, instead of having

-devAccounts per workload, will have separate Accounts per developer. I love this kind of setup, but it’s a lot of work to automate, and there is the support cost concern I mentioned above. Once you grow big enough it’s definitely something to consider though.

Account hierarchy

An Organization is a hierarchy of Accounts, where the Management Account is at the root. To start with you can safely have one level of Accounts below the Management Account - there’s no need to get more complicated than that initially.

A simple but scalable Account and hierarchy structure

Sub-hierarchies / Organizational Units (OUs) are useful when you start wanting to introduce service control policies or some more advanced automation. But you can always move Accounts around hierarchy later, so don’t worry about it on day 1.

Next steps

Once you have your plan of what Accounts you want then you need to create them … and I’ll explain how best to do that next time! The next article in this series also explains how to start thinking each Account’s root user, and how to secure that root user.

Since I want to explain AWS Org Ops more broadly, future articles will discuss Account delegation; basic audit logging; setting up SSO for human user management; multi-Account DNS; VPCs; and service (non human) Account access.

Summary

Everyone starts their AWS journey with a single AWS Account, which is both where you create your AWS resources, and how you pay AWS for their services. But everyone also starts with a single-Account AWS Organization.

For most companies it makes sense to add multiple Accounts to their Organization. They still get the benefit of one billing arrangement with AWS, but each Account acts as a security boundary and also a resource container with its own Account-wide quotas. Using different Accounts for different workloads and environments reduces risk of security problems, and accidental performance or availability issues with production applications.

AWS Organizations can scale to a huge number of Accounts, with extensive hierarchies, but for smaller companies I recommend a simple but scalable approach: have the management / billing Account do as little as possible; move company-wide resources like user management into an org-ops Account; use separate Accounts per workload and environment type; and keep your hierarchy flat.

Feedback + Questions

If you have any feedback or questions then feel free to email me at mike@symphonia.io, or contact me at @mikebroberts@hachyderm.io on Mastodon, or at @mikebroberts.com on BlueSky.